Brownfields to brightfields: Realizing the solar future on recovered land

Rhode Island is currently in the process of creating an inventory of every brownfield, landfill, and parking lot in the state in their search for new locations to harness solar power. Even here, in America's smallest state, the intersection of favorable economics and demand for carbon reducing solutions to address climate change makes scaling the number of solar installations in the U.S. inevitable. Meanwhile, finding suitable sites for greenfield development that don't involve environmental, aesthetic, or interconnection constraints, has become increasingly difficult.

In Vermont, practically the only way to build a larger net metering project is by utilizing what the legislation refers to as "preferred sites"; these are primarily landfills, brownfields, or other previously developed land such as parking lots, rooftops, and abandoned gravel pits. Maine recently enacted legislation that provides incentives for renewable energy projects located on preferred sites. This is to encourage the development of distributed generation projects in locations that are more preferable (out of the public eye), are on properties that may not have a higher or better use for local tax revenue, and utilize locations that are closer to where electricity is being consumed, thus better suited from an interconnection/grid stability standpoint.

In Vermont, practically the only way to build a larger net metering project is by utilizing what the legislation refers to as "preferred sites"; these are primarily landfills, brownfields, or other previously developed land such as parking lots, rooftops, and abandoned gravel pits. Maine recently enacted legislation that provides incentives for renewable energy projects located on preferred sites. This is to encourage the development of distributed generation projects in locations that are more preferable (out of the public eye), are on properties that may not have a higher or better use for local tax revenue, and utilize locations that are closer to where electricity is being consumed, thus better suited from an interconnection/grid stability standpoint.

The reuse of brownfields and landfills as host sites for larger solar arrays is a relatively recent phenomenon. As solar markets have matured, state policies have evolved - instead of encouraging renewable energy development everywhere, the industry now needs forward-thinking policies that focus on where to best site solar projects over the next several decades. This is a significant pivot, and not one without challenges. While brownfields and landfills can offer more preferable locations for solar arrays than typical greenfield land (from environmental, aesthetic, and grid quality standpoints), the nature of working on and around environmentally impaired soil and groundwater presents additional complexity and risk. As a result, the development and construction of these projects are generally more expensive than a similarly sized project on previously undeveloped land.

Increasing numbers of elected and regulatory officials are recognizing the value of more solar built closer to areas with greater population density. One of the best solutions is by turning brownfields to brightfields. As an example, the 2.2-megawatt South Burlington, Vermont landfill solar project produces over 2,600,000 kWh of clean electricity per year in one of the heavier load zones; that's the equivalent of nearly 400 typical New England homes. In signing onto a long-term contract, the City is also saving money on its municipal electrical costs, with projections for up to $5M in savings over the 25-year contract period. These savings are being rolled into additional energy efficiency and renewable energy generation projects for the City, under a revolving loan fund construct.

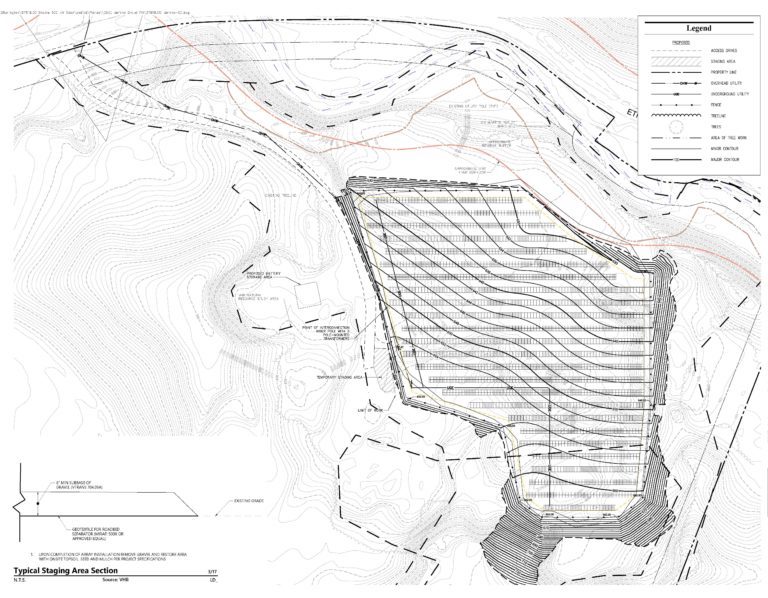

The 5.7-megawatt array installed last year on a Brattleboro, Vermont landfill is now generating nearly 7,000,000 kWh of clean electricity per year, $100,000 in annual lease revenue for the Windham County Solid Waste Management District, and significant savings on the electric bills for 20 schools, municipalities and other public institutions in the area - all through a group net metering arrangement. The total value to the community from this project is estimated to exceed $10M over the 20-year contract term. It's currently the largest landfill solar project in Vermont, and there will be more.

The 5.7-megawatt array installed last year on a Brattleboro, Vermont landfill is now generating nearly 7,000,000 kWh of clean electricity per year, $100,000 in annual lease revenue for the Windham County Solid Waste Management District, and significant savings on the electric bills for 20 schools, municipalities and other public institutions in the area - all through a group net metering arrangement. The total value to the community from this project is estimated to exceed $10M over the 20-year contract term. It's currently the largest landfill solar project in Vermont, and there will be more.

Conservative estimates predict a massive increase in the amount of solar installed in the U.S. by 2030. This will undoubtedly unlock the potential of underutilized sites such as brownfields and landfills; this land will be critical to realizing these ambitious but achievable projections. These sites will also be integral for meeting the increasing demand for electricity as we move toward electrifying the transportation and thermal energy sectors, while at the same time transitioning our energy supply system to a distributed generation model powered by renewable energy.

According to the Environmental Protection Agency, there are an estimated 450,000 brownfields in the United States. The National Renewable Energy Laboratory estimates that landfills and other contaminated sites cover 15 million acres across America, an estimated 80,000 of those acres of which have already been prescreened for renewable energy development.

As we embark on what some are referring to as "the Solar Decade," with plans to produce 20 percent of our domestic energy supply from solar by 2030, we can't afford to leave viable project sites empty. Turning brownfields into brightfields currently remains a relatively underutilized segment of the market. Although evolving technology drives down installation prices, and rapid innovation in the energy storage market helps to increase solar deployment, it's still not enough. Establishing local and state-level policies is critical to streamlining the development of these more complicated, yet often preferable projects.

Many of us in the solar industry are working hard to overcome these challenges by continuing to develop and construct brownfield and landfill projects; not just in Vermont, but across the entire country. Converting brownfields into brightfields creates opportunities for investors, the grid, and local communities by reclaiming unused land for clean energy generation where it is needed most, while offering savings to both taxpayers and ratepayers. And in our view, that is a win-win-win.

Chad Farrell is founder and chief executive officer of Encore Renewable Energy. Encoreworks to blend natural and built environments in creating commercial, industrial, and community-scale solar PV systems. They focus on undervalued and underutilized properties such as landfills, brownfields, parking lots, and rooftops.

Encore Renewable Energy | encorerenewableenergy.com

Author: Chad Farrell

Volume: 2019 September/October

.png?r=5673)