Page 38 - North American Clean Energy September/October 2019 Issue

P. 38

wind power

Wind Turbine

Gear Oils Protect

Against Wear

by Austin Guenther, P.E. and Eli Lester

Wind turbine gearboxes face severe operating conditions. In comparison to similarly-sized industrial gearboxes, wind turbine gearboxes have higher power densities, more variable loading, and experience wider operating temperature ranges. These conditions make selecting the right gear oil critical to maintaining wind farm availability and profitability.

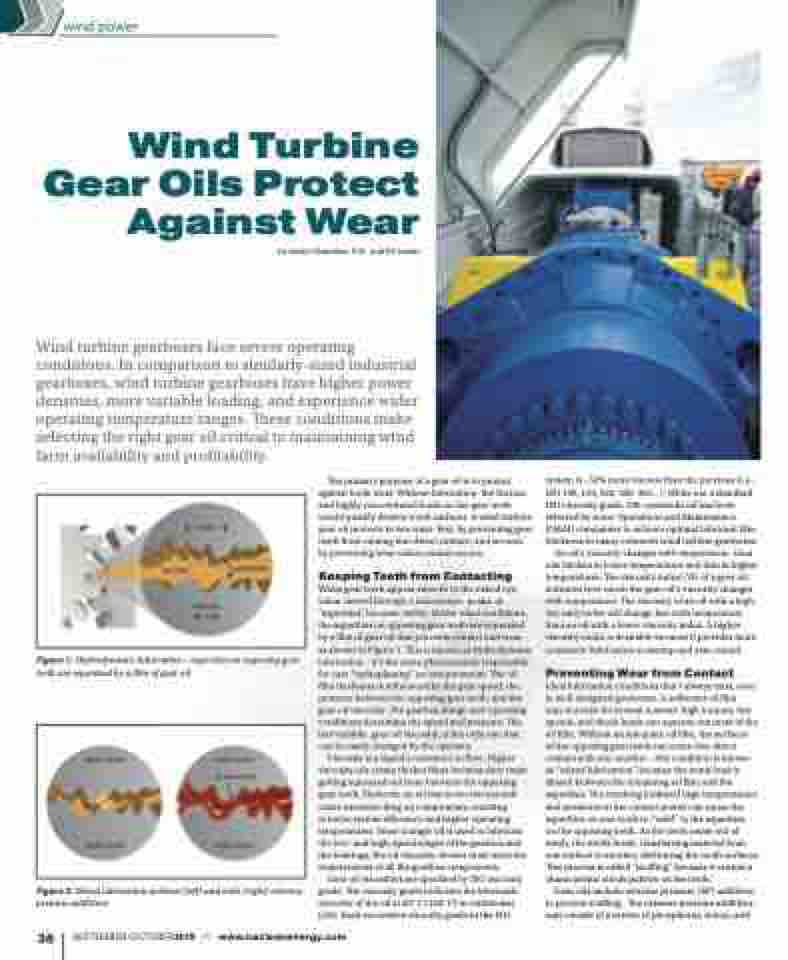

Figure 1: Hydrodynamic lubrication – asperities on opposing gear teeth are separated by a film of gear oil.

The primary purpose of a gear oil is to protect against tooth wear. Without lubrication, the friction and highly concentrated loads on the gear teeth would quickly destroy tooth surfaces. A wind turbine gear oil protects in two ways: first, by preventing gear teeth from coming into direct contact; and second, by preventing wear when contact occurs.

Keeping Teeth from Contacting

While gear teeth appear smooth to the naked eye, when viewed through a microscope, peaks, or “asperities”, become visible. Under ideal conditions, the asperities on opposing gear teeth are separated by a film of gear oil that prevents contact and wear, as shown in Figure 1. This is known as hydrodynamic lubrication – it’s the same phenomenon responsible for cars “hydroplaning” on wet pavement. The oil film thickness is influenced by the gear speed, the pressure between the opposing gear teeth, and the gear oil viscosity. The gearbox design and operating conditions determine the speed and pressure. The last variable, gear oil viscosity, is the only one that can be easily changed by the operator.

Viscosity is a liquid’s resistance to flow. Higher viscosity oils create thicker films because they resist getting squeezed out from between the opposing gear teeth. However, an oil that is too viscous will cause excessive drag on components, resulting

in lower system efficiency and higher operating temperatures. Since a single oil is used to lubricate the low- and high-speed stages of the gearbox and the bearings, the oil viscosity chosen must meet the requirements of all the gearbox components.

Gear oil viscosities are specified by ISO viscosity grade. The viscosity grade indicates the kinematic viscosity of the oil at 40° C (104° F) in centistokes (cSt). Each successive viscosity grade in the ISO

system is ~50% more viscous than the previous (i.e., ISO 100, 150, 220, 320, 460...). While not a standard ISO viscosity grade, 390 centistoke oil has been selected by some Operations and Maintenance (O&M) companies to achieve optimal lubricant film thickness in many common wind turbine gearboxes.

An oil’s viscosity changes with temperature. Gear oils thicken at lower temperatures and thin at higher temperatures. The viscosity index (VI) of a gear oil indicates how much the gear oil's viscosity changes with temperature. The viscosity of an oil with a high viscosity index will change less with temperature than an oil with a lower viscosity index. A higher viscosity index is desirable because it provides more consistent lubrication at startup and year-round.

Preventing Wear from Contact

Ideal lubrication conditions don’t always exist, even in well-designed gearboxes. A sufficient oil film

may not exist for several reasons; high torques, low speeds, and shock loads can squeeze out most of the oil film. Without an adequate oil film, the surfaces

of the opposing gear teeth can come into direct contact with one another - this condition is known as “mixed lubrication” because the tooth load is shared between the remaining oil film and the asperities. The resulting localized high temperatures and pressures at the contact points can cause the asperities on one tooth to “weld” to the asperities

on the opposing tooth. As the teeth rotate out of mesh, the welds break, transferring material from one surface to another, destroying the tooth surfaces. This process is called “scuffing” because it creates a characteristic streak pattern on the teeth.

Gear oils include extreme pressure (EP) additives to prevent scuffing. The extreme pressure additives may consist of a variety of phosphorus, boron, and

Figure 2: Mixed lubrication without (left) and with (right) extreme pressure additives.

38

SEPTEMBER•OCTOBER2019 /// www.nacleanenergy.com